|

|

Brazil: Body and Soul is a major exhibition showcasing the arts of Brazil from two key phases of their development, the Baroque (17th to early-19th centuries) and the Modern (1920s to the present). Brazil is a nation characterized by its diversity, and the exhibition presents a broad definition of the country's artistic culture, with emphasis on traditional religious and secular arts, arts of indigenous peoples, Afro-Brazilian contributions, as well as many Modern and contemporary visual forms of expression.

The complexity of visual culture in Brazil mirrors its vast size. Larger than the continental U.S., Brazil developed as a product of multiple layers of cultural inspiration. Even before the first contact with Europeans in 1500, the indigenous peoples in coastal and interior regions had created forms of personal adornment using feathers, cloth, and fibers. Contact with the Portuguese, who colonized Brazil and remained in power until 1822, brought styles of painting, sculpture, and architecture that were quickly adapted to meet the needs of the tropical locale. Later, immigration from other regions of Europe, and eventually East Asia, brought additional elements of cultural expression that were woven into the fabric of Brazilian society. Among the most important traditions were those imported by African slaves as early as the 16th century. Afro-Brazilian arts from the colonial and Modern periods are a significant component of the exhibition.

|

Brazil: Body and Soul begins with a "view from the outside"—depictions of Brazil by foreign artists in the 17th century. Frans Post and Albert Eckhout created the first representations of Brazil taken from life. They came to Brazil in 1636, and worked in a short-lived Dutch colony established near the cities of Recife and Olinda by the Dutch West Indian Company. The exhibition includes a number of important works by Post which have been described as the first American landscapes. The landscapes were created by the artist during his stay in Brazil and after his return to Holland. Brazil: Body and Soul begins with a "view from the outside"—depictions of Brazil by foreign artists in the 17th century. Frans Post and Albert Eckhout created the first representations of Brazil taken from life. They came to Brazil in 1636, and worked in a short-lived Dutch colony established near the cities of Recife and Olinda by the Dutch West Indian Company. The exhibition includes a number of important works by Post which have been described as the first American landscapes. The landscapes were created by the artist during his stay in Brazil and after his return to Holland.

The largest selection of Baroque art presented in the exhibition is three-dimensional and made of wood. There are many different regional sculptural styles. Examples from Bahia and other regions of the Northeast generally are very dramatic. Rio de Janeiro produced sophisticated sculpture with references to contemporary European (mainly Portuguese) models. Works made in Minas Gerais are elegant and frequently are painted in pastel colors. This region, which in the 18th century grew wealthy from gold and diamond mines, was the home of Brazil's best-known Baroque sculptor, Antônio Francisco Lisboa, also called O Aleijadinho (the Little Cripple) who is represented extensively throughout the exhibition.

While most of the Baroque sculptures in the exhibition were intended to be viewed in churches or chapels, others are representative of more private aspects of devotion including home altars and portable shrines, called oratôrios (oratories), or the small wooden images called ex-votos (a Latin term for something offered or performed in fulfillment of a vow). Ex-votos donated to churches or chapels are called milagres (miracles). They often take the form of body parts—heads, hearts, hands, stomachs, breasts—which signify that the person for whom the milagre was made had been cured of a malady specific to that area of

the body.

|

|

Brazil: Body and Soul also contains important examples of Baroque painting. Most of these are religious, including allegories of the Four Continents by 18th-century Afro-Brazilian painter José Theóphilo de Jesus and several large wood panels depicting scenes from the life of Saint Benedito, one of the many black saints venerated in Brazil. These pieces attest to the significance of the African impact on Brazilian society.

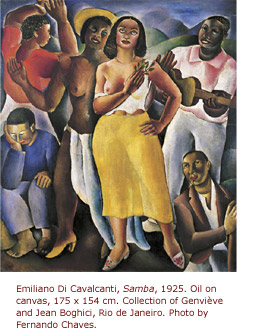

The later phase of Brazilian Baroque art, Rococo, is characterized by lively decorative form. Rococo painting, sculpture, and architecture styles survived into the early decades of the 19th century, after which artists embraced new European forms such as neoclassicism and romanticism. By 1900, São Paulo had become the economic and industrial center of Brazil due to its coffee trade. Large-scale immigration from Europe, and eventually from Japan, accounted for the city's rapid growth. It was in São Paulo that the Modernist movement originated in the 1920s, beginning with the famous arts festival Semana de arte moderna (Week of Modern Art) organized at the Teatro Municipal in February of 1922. Among the most important artists to emerge at this time were painters Emiliano Di Cavalcanti, Vicente do Rêgo Monteiro, and the sculptor Victor Brecheret. They had all spent time in Europe, specifically Paris, studying the latest trends in Modern art. Also included in this group is the most celebrated Modernist, Tarsila do Amaral. Tarsila, as she is invariably referred to in Brazil, spent a number of years in Paris with friends and teachers Constantin Brancusi, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, and André Lhote. An individual style developed in Tarsila's paintings executed between 1923 and 1930 that merged Cubism, Purism, and other contemporary trends with distinctly Brazilian themes and colors. She later turned toward social realism, influenced by her admiration for Soviet art and culture.

|

|

|

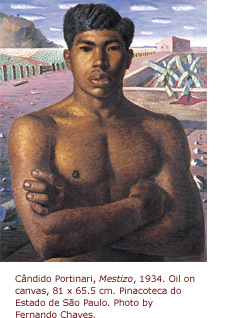

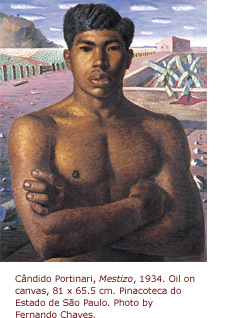

The art of the 1930s was marked, in part, by the political circumstances of Brazil. President Getúlio Vargas came to power as the result of a military coup. His dictatorship, known as the Estado Novo (New State), attempted to foster national pride among citizens, including artists such as Cândido Portinari, whose paintings of rural workers epitomized the social realism of the time. Another influence of the 1930s (and 1940s), Surrealism, inspired several key Brazilian artists including sculptor Maria Martins, who was well-known in New York, and Alberto da Veiga Guignard, whose landscapes of Minas Gerais possess a dream-like quality.

The evolution of painting and sculpture based on strict geometric proportions, termed Concrete art, began in the early 1950s. Concrete art—developed by Luis Sacilotto, Mary Viera, Franz Weissmann, and others—manifested the Brazilian engagement with a variety of international tendencies. Significant stimuli for Brazilian artists in the 1950s were the establishment of the first São Paulo Bienal in 1951 and the increased visibility of contemporary European art. By the end of the 1950s, the rigidity of the geometric exactitude and intellectualized approach of Concrete art gave way to the next phase of Modern art in Brazil. Neo-concrete art was practiced by Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape who argued for the importance of greater dynamism and an interactive physical engagement between works of art and the audience. Their pieces often took the form of clothing or other items people could touch and experience. The evolution of painting and sculpture based on strict geometric proportions, termed Concrete art, began in the early 1950s. Concrete art—developed by Luis Sacilotto, Mary Viera, Franz Weissmann, and others—manifested the Brazilian engagement with a variety of international tendencies. Significant stimuli for Brazilian artists in the 1950s were the establishment of the first São Paulo Bienal in 1951 and the increased visibility of contemporary European art. By the end of the 1950s, the rigidity of the geometric exactitude and intellectualized approach of Concrete art gave way to the next phase of Modern art in Brazil. Neo-concrete art was practiced by Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape who argued for the importance of greater dynamism and an interactive physical engagement between works of art and the audience. Their pieces often took the form of clothing or other items people could touch and experience.

The panorama of Modern Brazilian art also includes the work of many masters who fall outside of the conventional historical (often Eurocentric) categories of art. Arthur Bispo do Rosario, a visionary artist who created splendidly enigmatic cloaks, sashes, and other textile pieces, had no artistic training and developed his work while a patient at the Juliano Moreira Colony for the mentally ill in Rio de Janeiro. Other artists employ religion as the force behind their innovations. Mestre Didi and Ronaldo Rego are associated with the Afro-Brazilian religions of Candomblé and Umbanda respectively, and their objects and constructions are spiritually charged in a highly emotional way. Still other 20th-century artists such as Agnaldo Manoel dos Santos and Geraldo Teles de Oliveira (GTO) carry on a dialogue in their work with traditional African forms of wood carving.

Contemporary Brazilian artists have formed an integral part of international art culture in recent years. Brazil: Body and Soul does not present a comprehensive overview of the developments of the past decade. The selection of contemporary artists is intended to suggest some of the many artistic strategies and visual vocabularies used today—installation, sculpture, photography, and references to traditional painting. The artists Antonio Manuel, Vik Muniz, Ernesto Neto, Lygia Pape, Miguel Rio Branco, Regina Silveira, Tunga, and Adriana Varejão establish vital parallels with the art of the past, and constitute critical links in a fundamental dialogue with the continuing, fluid narrative of artistic expression in Brazil.

—Edward J. Sullivan, Curator

|

|

Brazil: Body and Soul begins with a "view from the outside"—depictions of Brazil by foreign artists in the 17th century. Frans Post and Albert Eckhout created the first representations of Brazil taken from life. They came to Brazil in 1636, and worked in a short-lived Dutch colony established near the cities of Recife and Olinda by the Dutch West Indian Company. The exhibition includes a number of important works by Post which have been described as the first American landscapes. The landscapes were created by the artist during his stay in Brazil and after his return to Holland.

Brazil: Body and Soul begins with a "view from the outside"—depictions of Brazil by foreign artists in the 17th century. Frans Post and Albert Eckhout created the first representations of Brazil taken from life. They came to Brazil in 1636, and worked in a short-lived Dutch colony established near the cities of Recife and Olinda by the Dutch West Indian Company. The exhibition includes a number of important works by Post which have been described as the first American landscapes. The landscapes were created by the artist during his stay in Brazil and after his return to Holland.

The evolution of painting and sculpture based on strict geometric proportions, termed Concrete art, began in the early 1950s. Concrete art—developed by Luis Sacilotto, Mary Viera, Franz Weissmann, and others—manifested the Brazilian engagement with a variety of international tendencies. Significant stimuli for Brazilian artists in the 1950s were the establishment of the first São Paulo Bienal in 1951 and the increased visibility of contemporary European art. By the end of the 1950s, the rigidity of the geometric exactitude and intellectualized approach of Concrete art gave way to the next phase of Modern art in Brazil. Neo-concrete art was practiced by Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape who argued for the importance of greater dynamism and an interactive physical engagement between works of art and the audience. Their pieces often took the form of clothing or other items people could touch and experience.

The evolution of painting and sculpture based on strict geometric proportions, termed Concrete art, began in the early 1950s. Concrete art—developed by Luis Sacilotto, Mary Viera, Franz Weissmann, and others—manifested the Brazilian engagement with a variety of international tendencies. Significant stimuli for Brazilian artists in the 1950s were the establishment of the first São Paulo Bienal in 1951 and the increased visibility of contemporary European art. By the end of the 1950s, the rigidity of the geometric exactitude and intellectualized approach of Concrete art gave way to the next phase of Modern art in Brazil. Neo-concrete art was practiced by Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape who argued for the importance of greater dynamism and an interactive physical engagement between works of art and the audience. Their pieces often took the form of clothing or other items people could touch and experience.