|

|

|

|

Order the catalogue |

|

Goncharova manifested her radicality in

both life and art. She shocked the Moscow bourgeoisie with

her casual cross-dressing and her open cohabitation with

artist Mikhail Larionov, and elicited the anger of the

righteous with her brazen interpretations of religious

subjects such as The Evangelists (in Four Parts),

1911. Not unexpectedly, she was the victim of hostility and

disparagement in the press, and the official censor forced

her paintings to be withdrawn from more than one

exhibition. Goncharova manifested her radicality in

both life and art. She shocked the Moscow bourgeoisie with

her casual cross-dressing and her open cohabitation with

artist Mikhail Larionov, and elicited the anger of the

righteous with her brazen interpretations of religious

subjects such as The Evangelists (in Four Parts),

1911. Not unexpectedly, she was the victim of hostility and

disparagement in the press, and the official censor forced

her paintings to be withdrawn from more than one

exhibition. |

|

|

Goncharova's vivid paintings of industrial

machinery, the local countryside, and peasants and pagan

effigies (including Sabbath, 1912, and The

Evangelists), demonstrate the breadth of her subject

matter and the richness of her vision. While she was aware

of French painting after Impressionism, especially the work

of Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse, Goncharova derived true

inspiration from the indigenous traditions of medievel

Russian art. In the Russian icon, for example, she

discovered new perceptions of space, anatomical proportion,

and color combinations, which she then applied to her own

studio paintings, book illustrations, and stage designs.

She also looked at peasant embroidery, the lubok

(hand-colored print), and even the stone baba or

stellae, examples of which dotted the Russian and Ukrainian

landscape. Peasants Gathering Grapes, 1912, is a

convincing paraphrase of this particular ethnographic

concern. Goncharova's vivid paintings of industrial

machinery, the local countryside, and peasants and pagan

effigies (including Sabbath, 1912, and The

Evangelists), demonstrate the breadth of her subject

matter and the richness of her vision. While she was aware

of French painting after Impressionism, especially the work

of Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse, Goncharova derived true

inspiration from the indigenous traditions of medievel

Russian art. In the Russian icon, for example, she

discovered new perceptions of space, anatomical proportion,

and color combinations, which she then applied to her own

studio paintings, book illustrations, and stage designs.

She also looked at peasant embroidery, the lubok

(hand-colored print), and even the stone baba or

stellae, examples of which dotted the Russian and Ukrainian

landscape. Peasants Gathering Grapes, 1912, is a

convincing paraphrase of this particular ethnographic

concern.

|

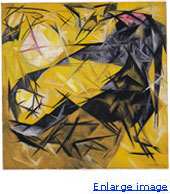

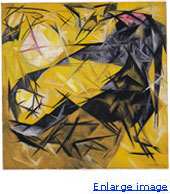

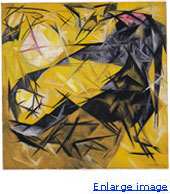

Top right: Cats (rayist percep.[tion]

in rose, black, and yellow), 1913. Oil on canvas, 84.5

x 83.8 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 57.1484.

© 2000 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP,

Paris. Top right: Cats (rayist percep.[tion]

in rose, black, and yellow), 1913. Oil on canvas, 84.5

x 83.8 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 57.1484.

© 2000 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP,

Paris.

|

Above: Photograph of Goncharova and

Mikhail Larionov made up for a Furturist theater project,

1913. Reproduced in Teatr v karrikaturakh (Moscow),

no. 3 (Sept. 21, 1913), p. 9.

|